Gen’l,

The War was not over by Christmas, like some of the more optimistic Engineer Corps officers made you believe earlier. But as the last full development year of the game draws to an end, it’s time to take a quick peek at the campaign side of the game. Sometimes a few images tell more than a wall of text, so let’s jump right into it!

In Command of the Armies.

In the campaign, player takes a role in the high command of his chosen side’s leadership. In the above image you can see the power balance between North and South – this balance is what you are trying to tip over to your favor! Here, playing as the Union, good ‘ole Honest Abe is running the show, with good, though a lot older All-American was hero Scott in command of the northern armies. Most important thing is to keep the morale of the citizen and support high. Only this way can the Union rely on volunteers to fill the ranks, and the citizen to keep carrying the weight of the war. The listed numbers control this balance, so winning battles is just one part of the puzzle, that the population is trying to figure out from the news.

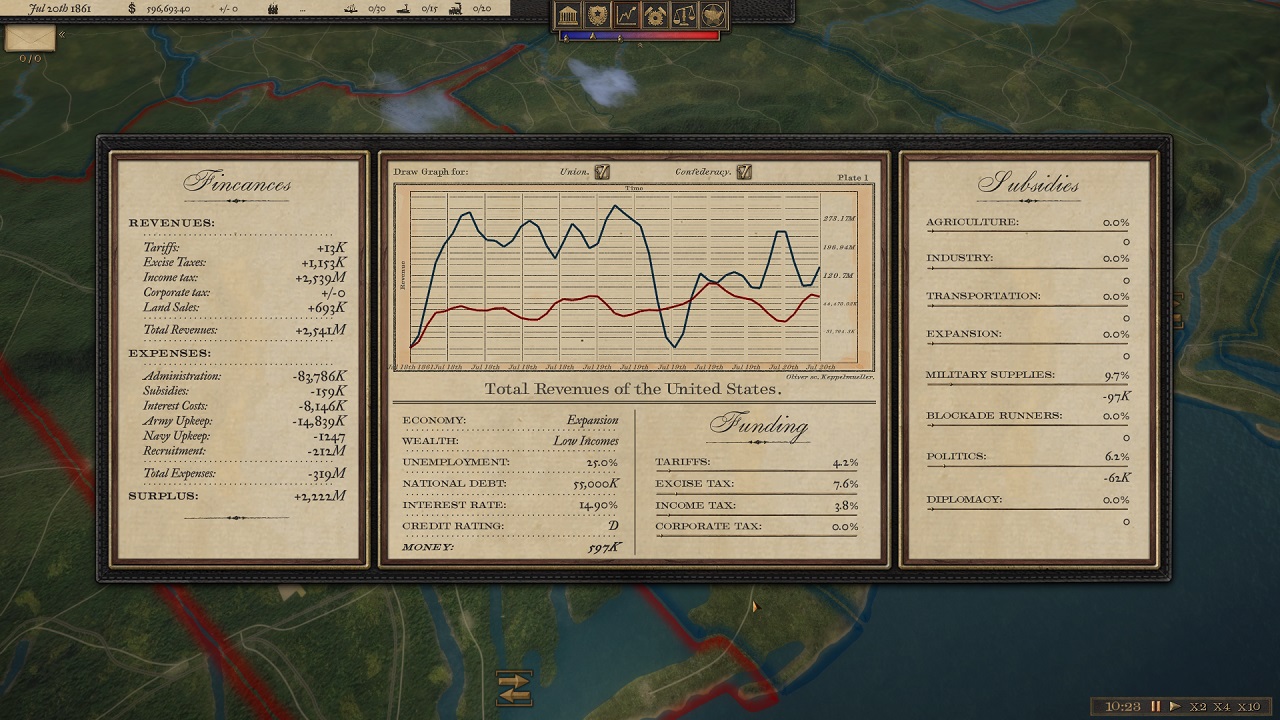

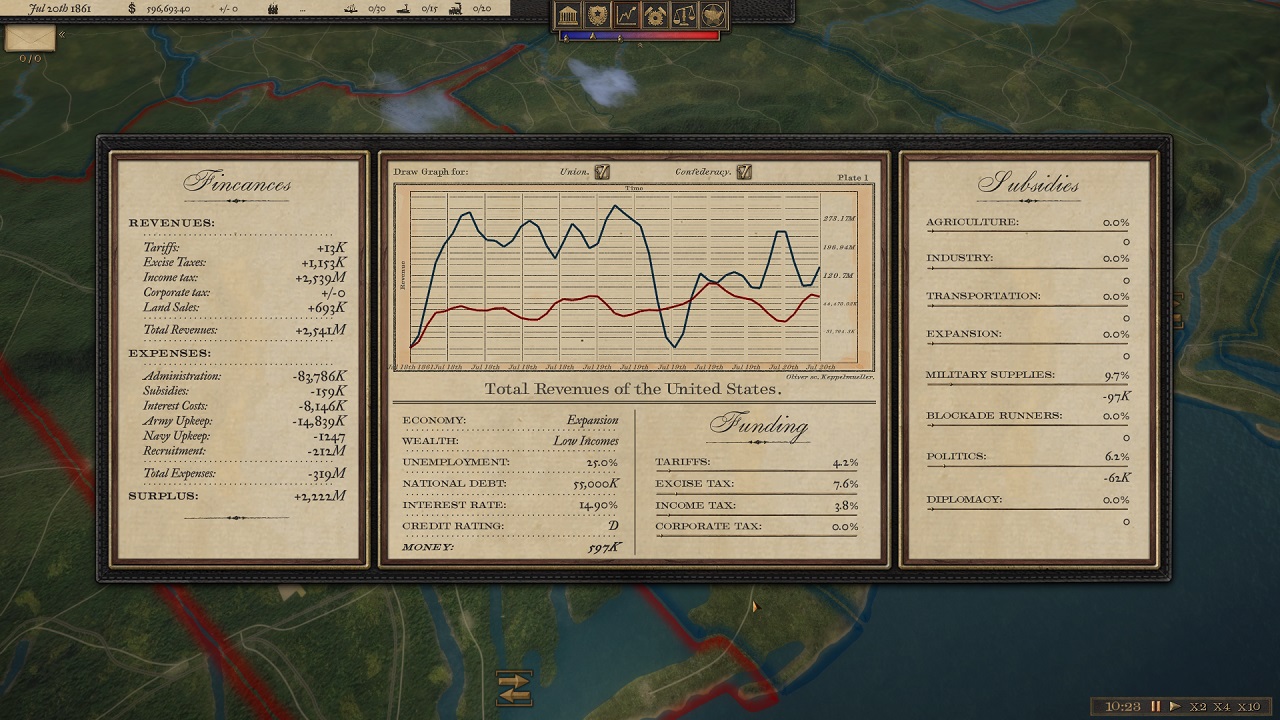

As it’s 1861, the means for funding the war are quite different from to-day:

Your government is funded by land sales and taxes, and by loans and bonds when needed. As the player, you can influence how funds are collected and then distributed – or you can leave this to the all-so-trustworthy politicians (automanage). After the fixed costs of military upkeep, the surplus can be diverted as government subsidies to support the kind of policies you choose to follow. More about the policies later. You can also compare the economic success with that of the foe.

The Theaters of War.

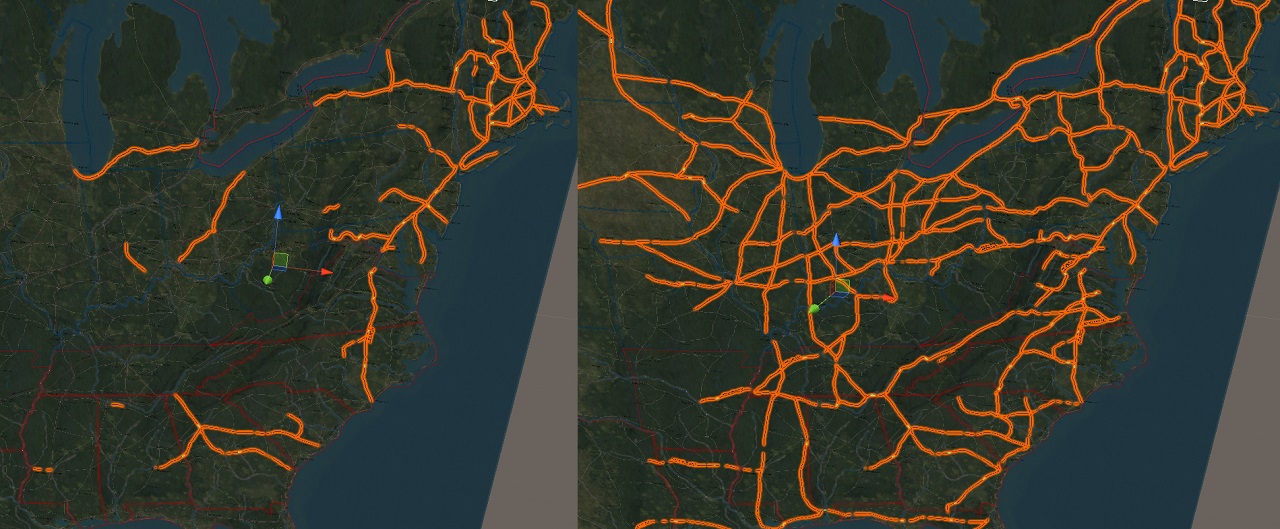

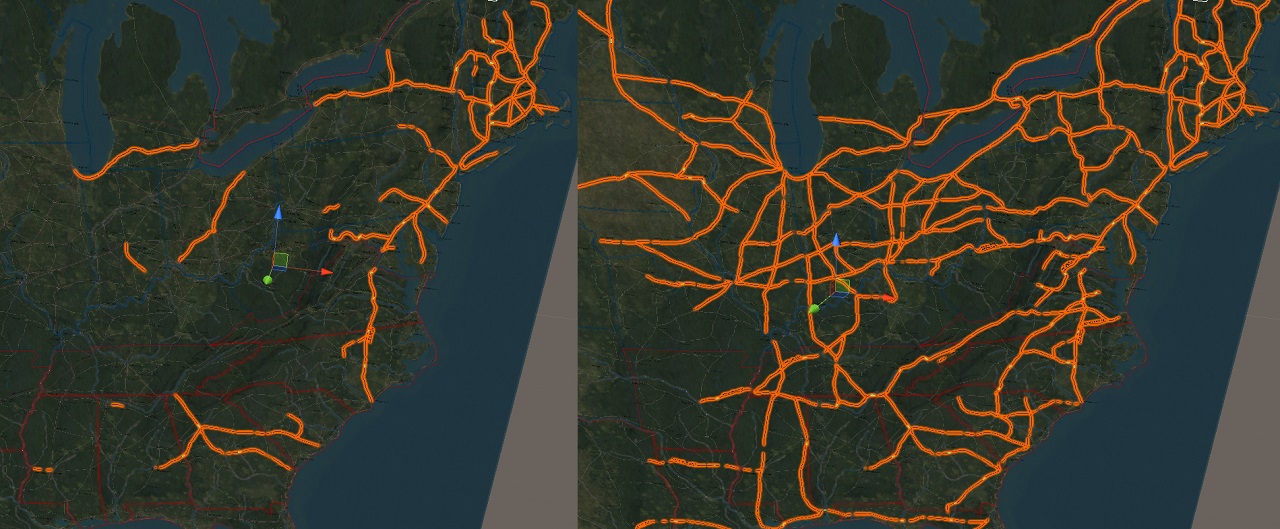

In the game, the campaign takes place on an epic campaign map, spanning from Maine to Texas, from Florida to Dakota territory. The map is created from period surveys, and most important routes can be seen dotting the countryside, along with hundreds of towns, ports, ferries… The rail lines can be expanded during the game, too, as can be seen in this comparison picture (also from editor) from 1850 to 1865:

And below is the campaign map in action. You see the roads and rail lines, along with canals, mountain passes and ferries – and the dynamic weather system creating different weather on different parts of the map.

On this fine July day, the General, whose name is on every lips right now, and in a good way for now, does not need to worry about rain and muddy roads. Though he may be worried more about the untrained troops he is going to lead into battle soon, in the scorching heat.

When zooming out from the terrain, you, again, can use the paper map to see the big picture. When zooming all the way out, you have also tools to visualize how the campaign map lives behind the scenes. While you can see the state lines running neatly in the map, this is not the military reality. To see who is in command of what areas, player can choose to view the dynamic front lines, as they move. Here you can, for example see, how controlling forts in Virginia places parts of that state and North Carolina under Union control – a true thorn in the side. When the armies move and cities are conquered, the front lines move as well. Area and infrastructure under your control is blocked from the enemy to use freely – this includes and allows cutting supply lines!

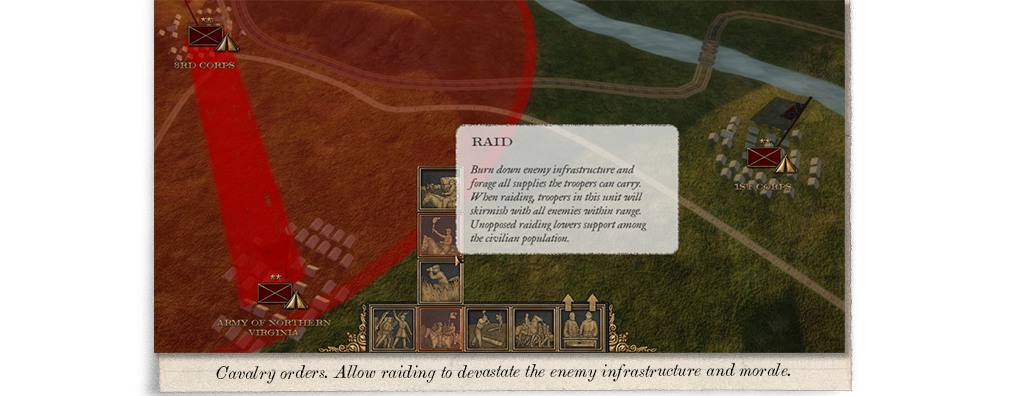

Here Patterson, who still is one of the top Generals in Union Army, has his troops camped on the northern entry to Shenandoah Valley, over watching Harper’s Ferry. As the town is under Union command, northern supplies and trade flow there freely. In case it would be blocked by the Confederates of Johnston, the flow of supplies would cease, and the transport capacity in this area would suffer. This means raiding will be an important tactic, which will not only deny the enemy important routes for the time being, but will also effect the area for a longer time, as replacing equipment, roads, railroads, etc. are needed. A well placed raid deep into enemy territory could have severe consequences, not only in cutting supply lines, but also affecting the morale and support of the population in the longer term!

Here, on the map, Union Army intelligence gathering is shown in a heat-map. Though McDowell rates his intelligence as excellent, he has no idea what is happening beyond the Confederate armies, and even the information about those armies is sketchy. Also seen are the combat and command radii of the army. Within the combat radius (inner circle), enemy units are engaged if the unit stance is set to offensive – if defensive, the unit will stop and start digging in. Within the command radius (outer ring) other armies can reinforce this army, in case it goes to battle. Though, the further away the other armies are, the longer it takes for them to reach the battlefield. In this position it’s even possible that Johnston’s Army would reach Manassas quicker than Patterson? Patterson could move in and hold Johnston in place (both on defensive stance and close together will fortify positions and are considered “locked” to one another), but if he’s cunning, he could slip away regardless?

In the Chesapeake Bay, Union has a fleet ready to sail out to meet the Confederate Navy, or to support land operations by bombarding forts or escorting transports to, say, the Peninsula? But who would go on that God-forbidden swampy wasteland? At least any time soon…

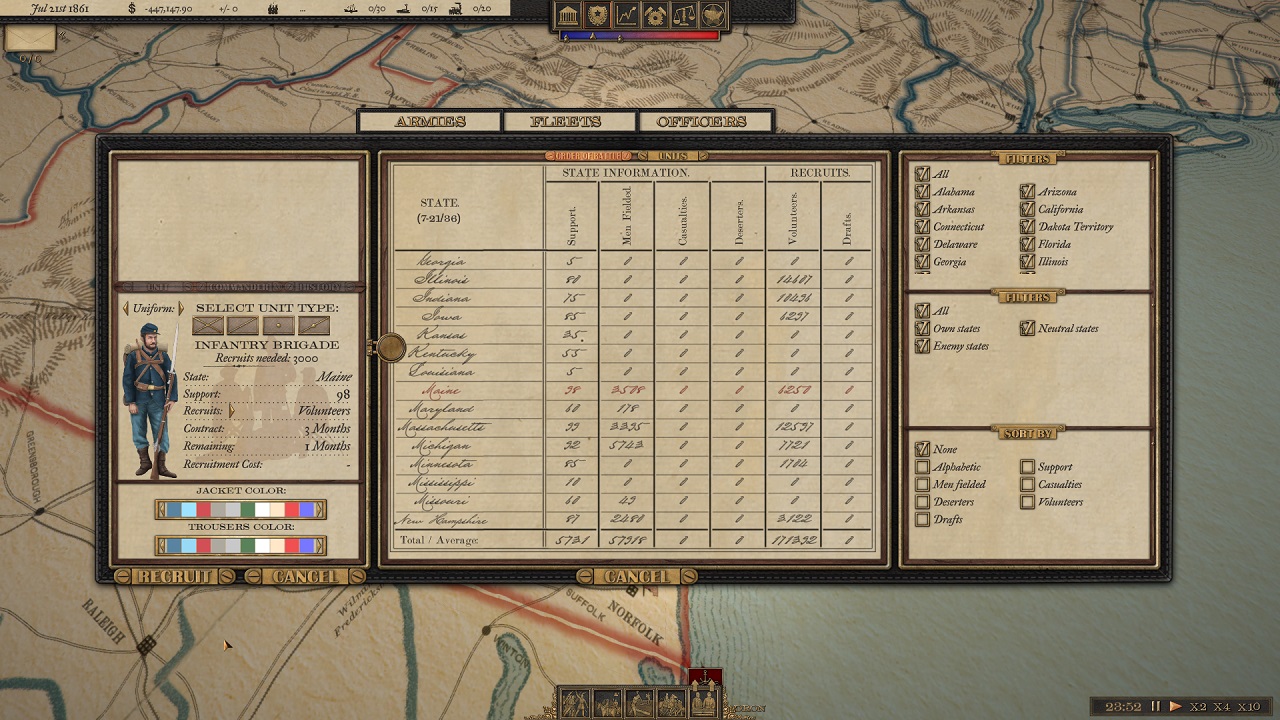

Army Management Made Easy.

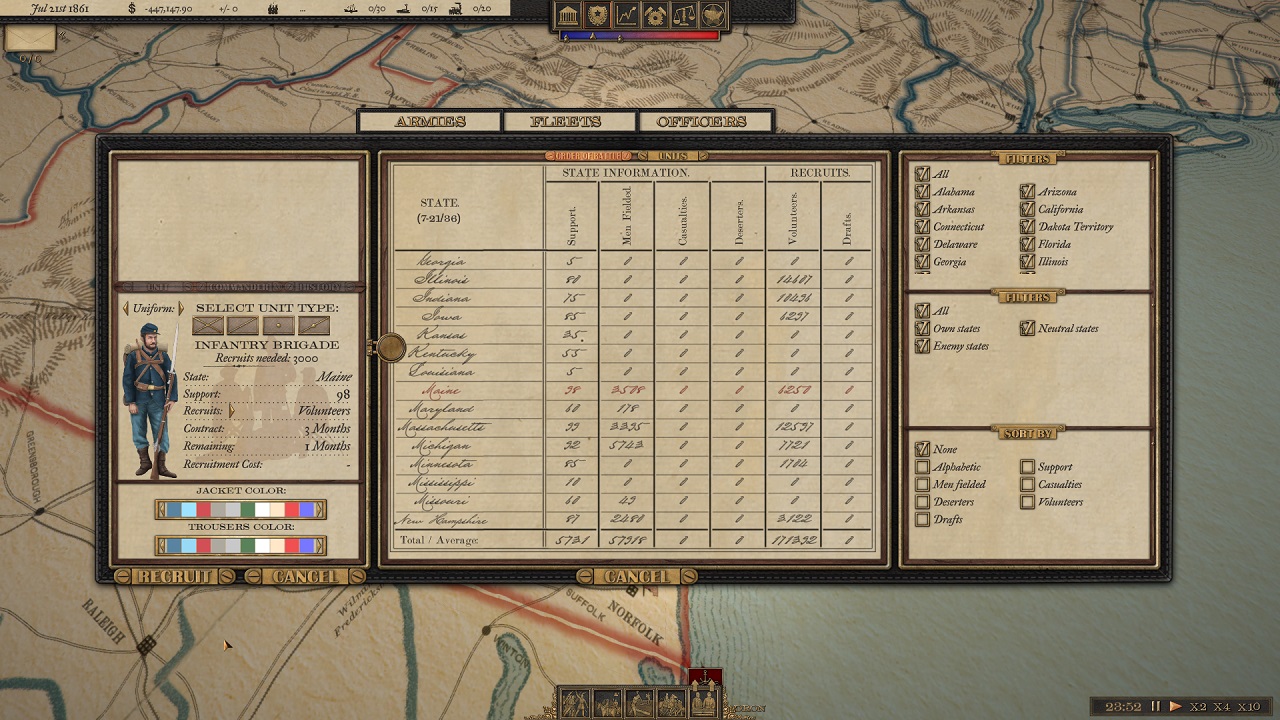

Keeping the armies in shape for fighting is vital. This means also recruitment and management. Here McDowell’s ranks are bolstered with a new Brigade. Volunteers are available where support is high, and population is available. States can, and will, provide troops for both sides of the war if the population’s support is divided. At least in Maine the rebel cause has not won many hearts, so the recruits will be heading to D.C. in blue uniform. But only for 3 months for now, as that’s what Abe said it would take to quell this pesky rebellion – and that’s how long the contract is.

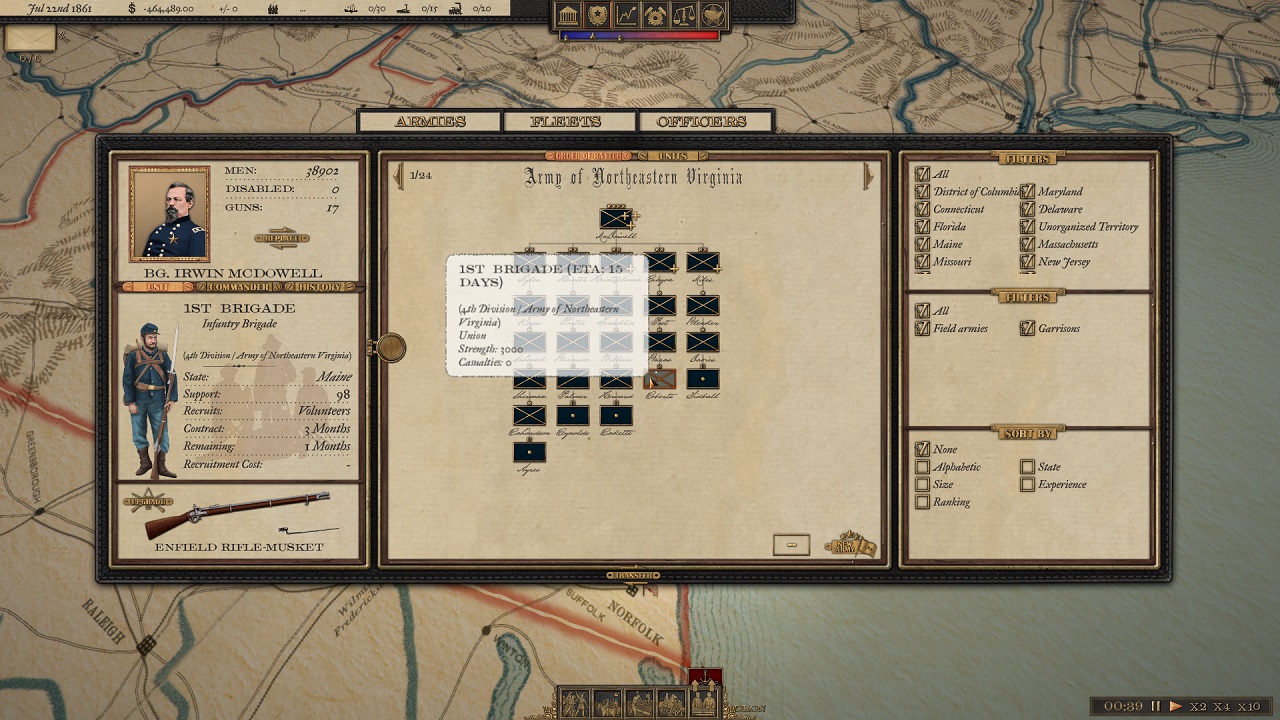

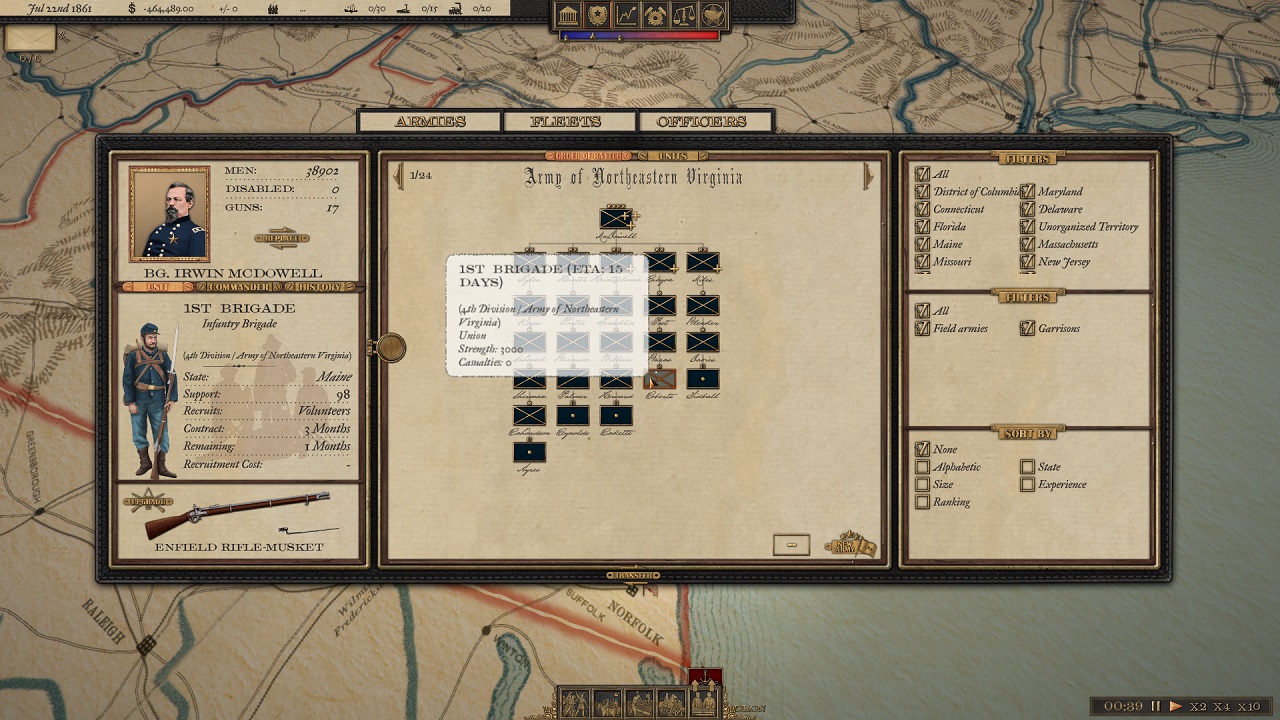

Once the required regiments are mustered, the shiny new brigade will march to join McDowell’s 4th Division under Runyon. Depending on distance, the time can be from days to weeks. Commanders can also transfer units within the army, or between armies, by simply dragging and dropping, and off they march:

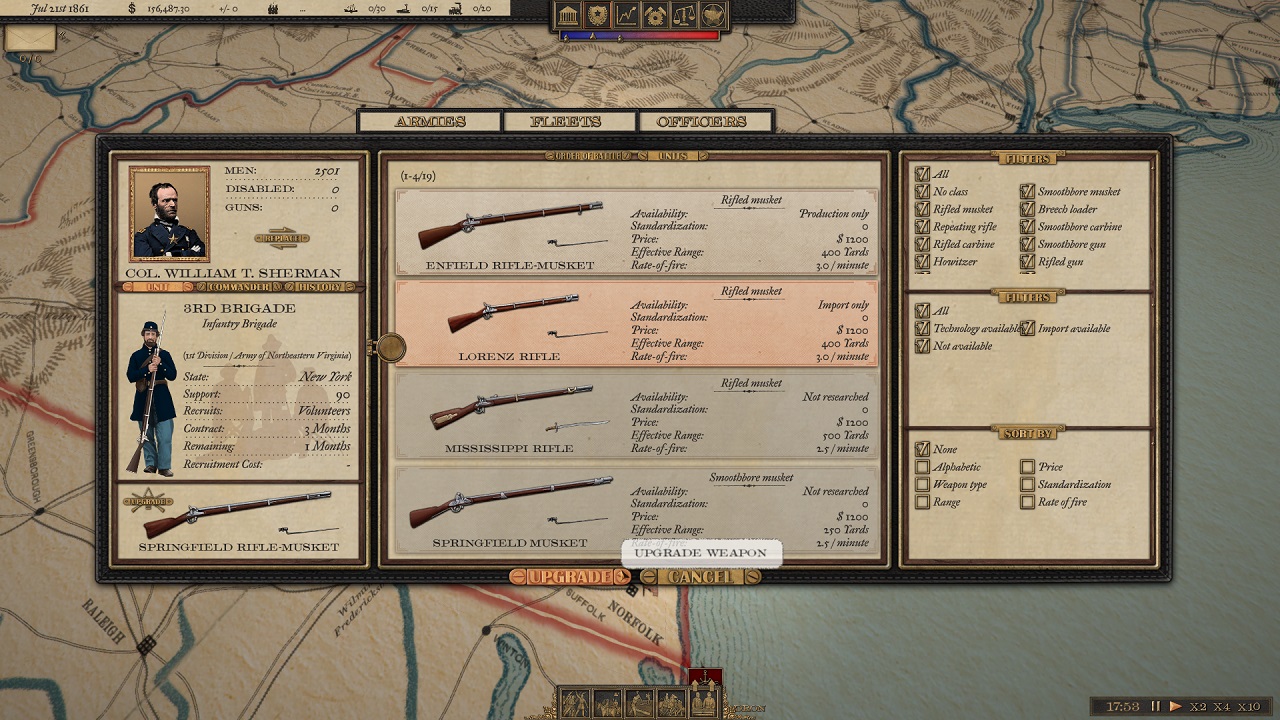

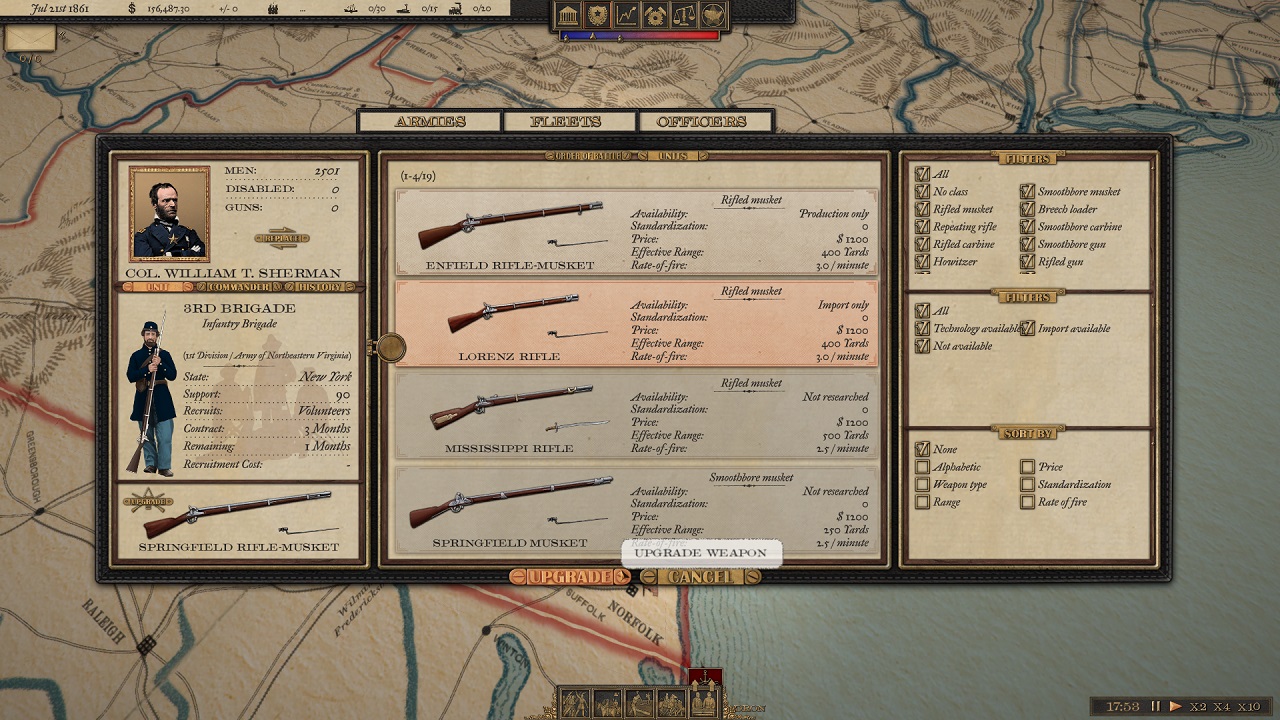

And in case you’re not happy with the weapons the unit is carrying, upgrading is possible. But bear in mind, you will need functioning weapon industry or good relations with European superpowers willing to export their weapons. Standardization plays a role, so throwing expensive repeating rifles at every unit is – in addition to complete waste of ammunition – handled within the economy.

OK, that’s it for this year, General! More campaigning will be coming your way soon! Have a Happy New Year!

Most Respy,

Gen’l. Ilja Varha,

Chief Designer, &c.