In “GT2” (working title), in the reworked battle layer, we’ve adjusted the command and control logic a bit to allow further tactical flexibility in the gameplay. Like before, order delays (couriers carrying the commanders’ orders along the chain of command) are complicating things, but there are more options on how to use the commanders during a battle and the units have a bit more initiative (when allowed).

Military Hierarchy and Order Delays

Like in The Civil War (“GT1”), an army is built into a military hierarchy, forming an order of battle. In the bottom are the units: these are the playable single entities on the battlefield (GT1: brigades and artillery battalions). Multiple units can be organized into a group, with its own commander. Multiple groups can be further grouped together with their own commander, and these placed under the army commander.

This hierarchy forms the basis for command and control. When an order is given to a unit, the order must travel through the organization and the appropriate commanders before reaching the unit for execution. So far nothing new.

The first change comes with the couriers delivering the orders. This time around they will avoid the enemy, which may complicate their journey. It is possible the courier does not manage to reach his target, which effectively can lead to part of your army being out of your control, at least for a short while. Trying to find the recipient in thick smoke or disorganized close combat may also slow down the delivery of your orders.

Command and Control

In the new system, commanders have their own small headquarters/escorts that not only point out their location and act as order delay nodes (as in GT1), but are combat elements. These elements are attached to units during the battle, and their positioning can be easily adjusted to enable improved command and control where needed.

When a commander is with a unit, he is able to give orders directly to the unit, which speeds up things considerably, eliminating the need for delivery of written orders. The commander can only embed himself in units under his command. And of course, if commanders are close to one another, orders are delivered faster. The unit the army commander is with reacts the fastest, as the orders don’t need to be distributed further.

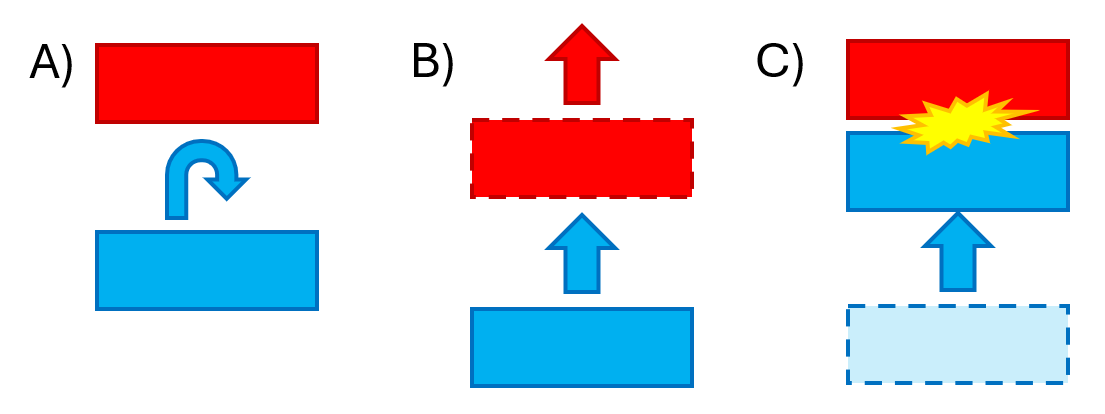

This allows forming a point of main effort where order delays are shorter, if needed. Also, having the commanders in the thick of battle with their men will increase motivation (while also increasing the chance of commander casualties). Of course, if you, for example, have the commanders focus on running the battle of the right wing, the left wing will be slower to control. These images provide a comparison between two optional use of commanders, with their pros and cons:

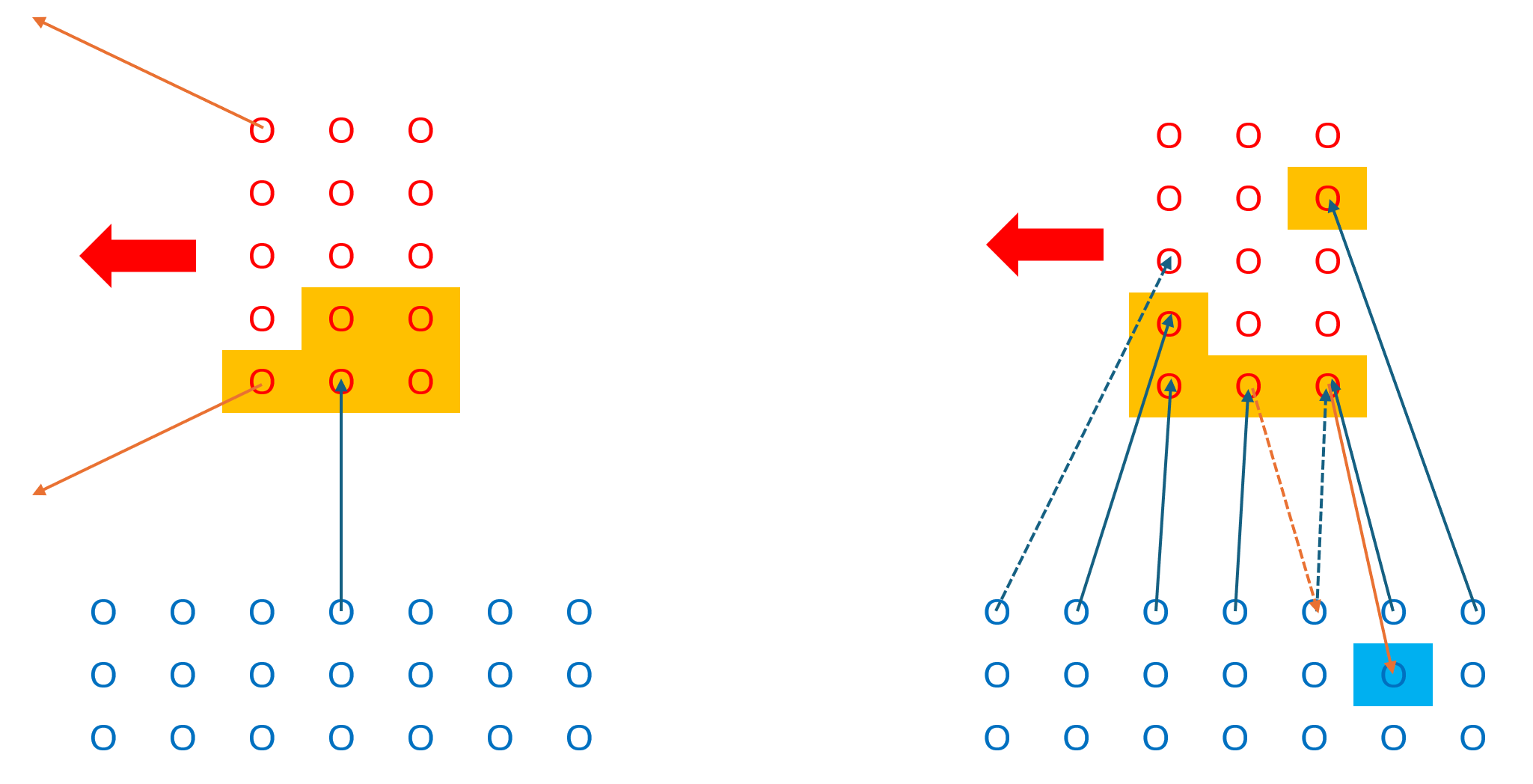

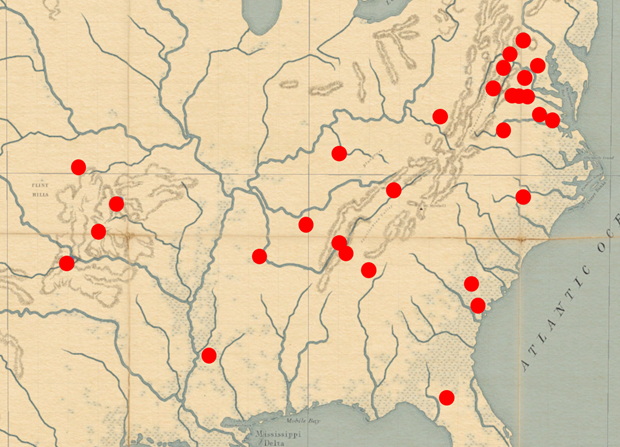

Situation:

Your army (blue) is facing the enemy (red), and an opportunity presents itself: At the extreme right flank you have a cavalry brigade of a cavalry division, that is in position to turn the enemy flank. Time is of the essence before the enemy can reinforce this flank and empty your plans.

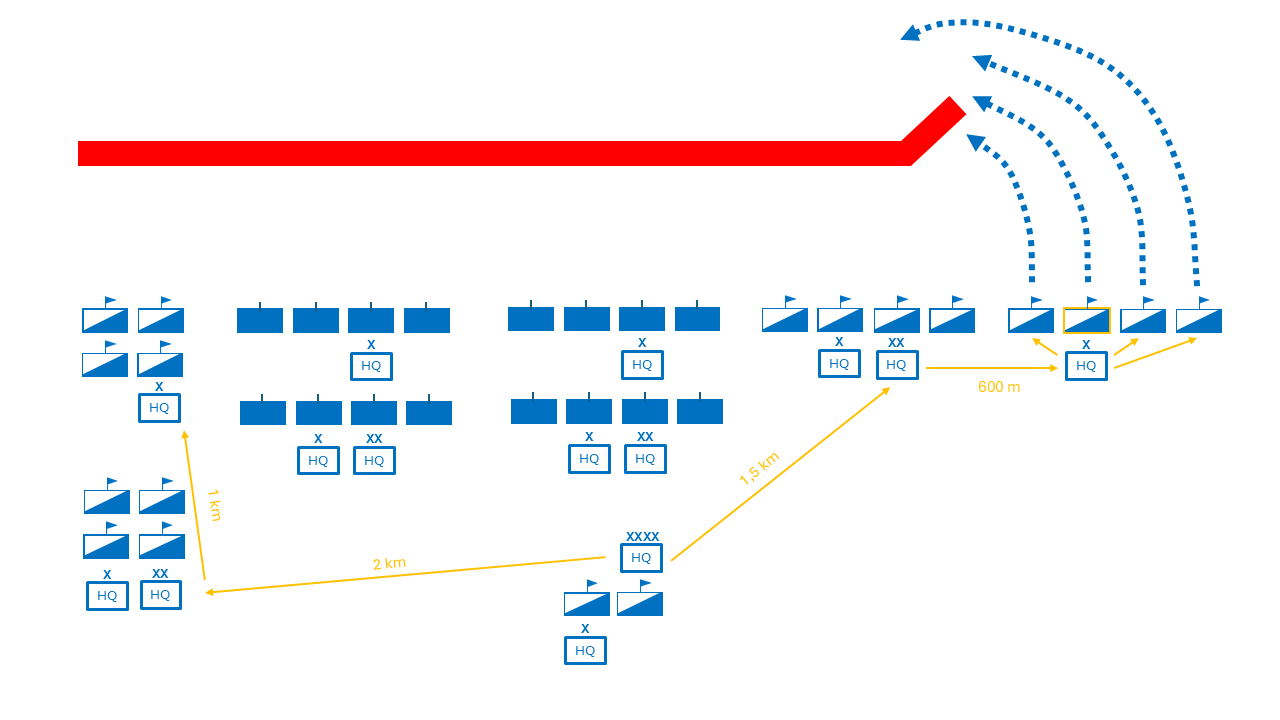

Option A: Central command.

Here your army commander is in a central, balanced location, deployed with the army reserves a safe distance from the front. In this situation, in total, we have 5 written orders, and 5 couriers covering a total of 2+ kilometers. This takes time. On the other hand, if the army commander needs to send orders to the brigade in the 1st echelon of the left flank, the delay would be similar.

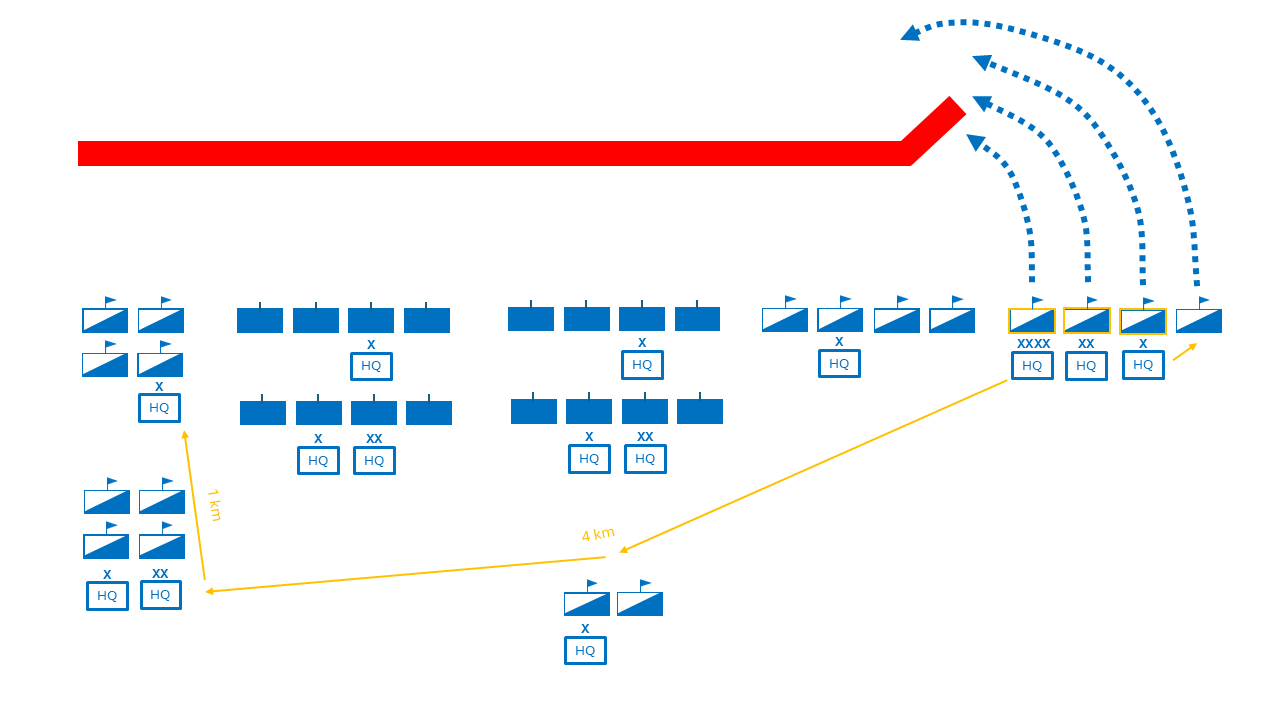

Option B: Commanding from the front.

Here the army commander decides to command the flanking move personally. He has placed himself in the brigade in question, and also takes the division commander with him. In total, we have 3 written orders, and 3 couriers covering a total of a few hundred meters at most. This takes very little time (in comparison to option A), the attack commences shortly, and the command and control of the wing during the attack is excellent. The con is, if the army commander would need to send orders to the units in the other flank of the army, there would be 4 kilometers to cover. And if the flanking move is successful, the army commander may find himself behind the enemy line, from where the courier would need to run a long detour, further increasing delay.

And of course there’s the higher possibility of lead poisoning for your brave commander…

Units’ Initiative

In GT1, stances are given to group commanders, who in turn will give orders to their units according to situation and instructions by player (like formation, etc.). In GT2 stances are moved a step down to unit level. This increases the initiative of the units and results in more appropriate and timely reactions to surrounding conditions during a battle.

Players can set a stance to each unit individually, or per group. There’s also an option to order the unit commander to “follow my specific orders”, which means the player can (and must!) control every aspect of the unit’s behavior, but this of course is subject to order delays. When given a stance, a unit will act independently.

This independent activity includes choice of formation, engagement range and firing system used, movement speed, limbering/mounting and detaching skirmishers. These are also carried over to any elements attached to the unit, such as supporting regimental guns.

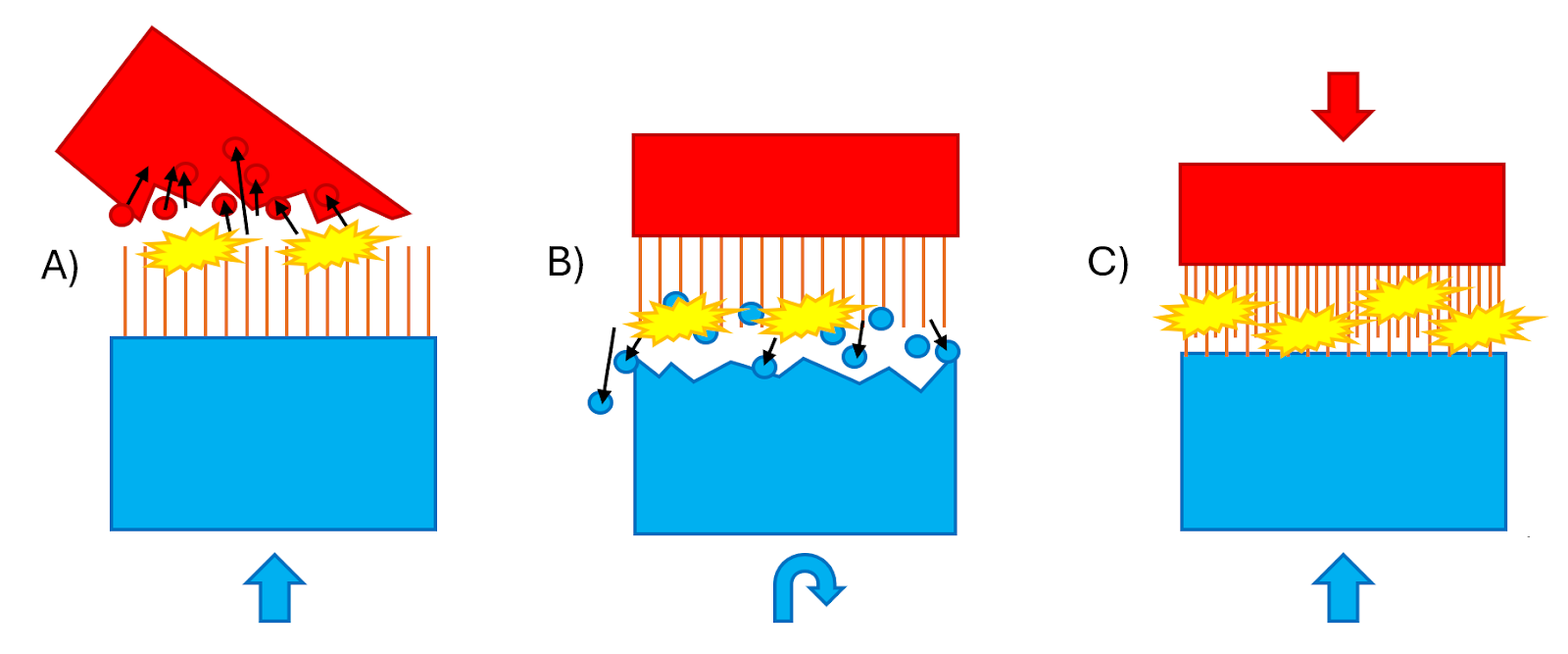

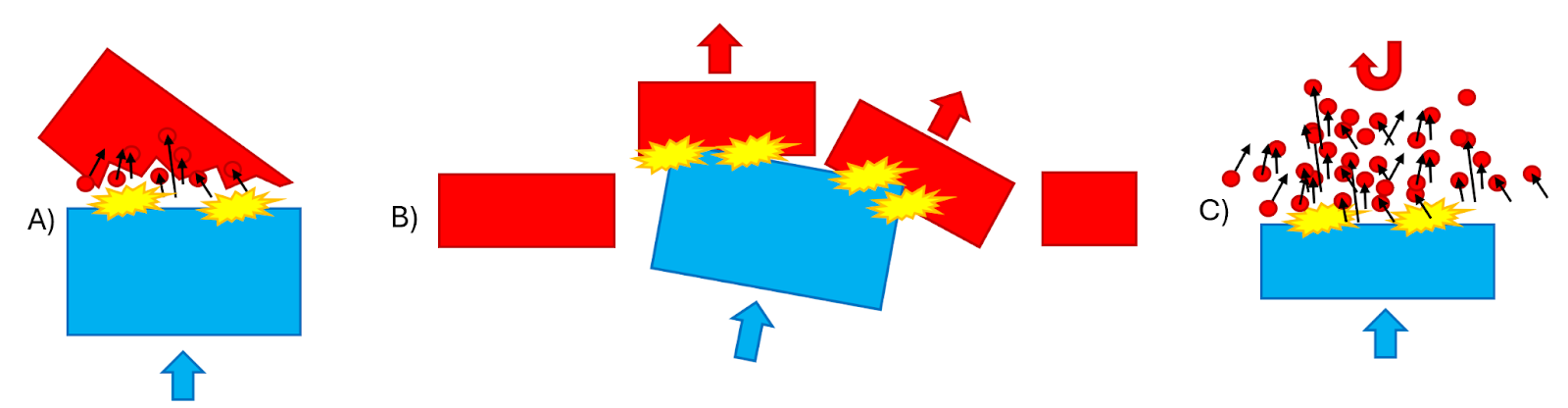

In GT1 the stances are Screen, Defend, Attack and Assault. In GT2 the toolbox is expanded, and the available stances are to Skirmish, Hold ground, Counter-charge, Attack, Assault and Reserve. Examples of such initiative, when ordered to attack:

- when moving out, the unit may deploy skirmishers to mask the movement

- crossing difficult terrain, the unit may adapt formation accordingly, for example from a line to column where alignment is easier to maintain and movement generally faster

- at long distance the unit may engage enemies with volleys by sub-units (like platoon) to maintain pressure and control ammo consumption since accuracy is limited due to range

- closing up with the enemy, the unit may form line and start firing by rank or even full unit volleys to maximize shock effect

- if the enemy is weak, the unit may choose to charge into melee to break the enemy line, and to do it using an attack column if the enemy formation is fragmented

- if the charge fails, the unit may fall back and switch to defensive if morale falters, or to try again once recovered

- in case the charge succeeds, and if in condition to still do so, the unit may press on and pursue the broken enemy, inflicting further casualties or even forcing it to surrender.

Most Respy,

Gen’l. Ilja Varha

Lead Designer – Grand Engineer Corps